Europe's perfect storm

Another reason to be worried is that Europe faces not one crisis, but several. The first is economic: not just the current reality of slow growth, but the prospect that slow growth will continue without respite, owing above all to policies that often discourage businesses from investing and hiring. The rise of populist political parties of both the left and the right across the continent attests to popular frustrations and fears

The Chinese often point out that in their language the character for crisis and opportunity are one and the same. But, while it is indeed true that crisis and opportunity often go hand in hand, it is difficult to see much opportunity in Europe’s current circumstances.

One reason the current situation facing Europe is so difficult is that it was so unexpected. Here we are, 70 years after the end of World War II, a quarter-century after the end of the Cold War, and some two decades after the Balkan wars, and suddenly Europe’s political, economic, and strategic future seems much more uncertain than anyone predicted as recently as a year ago.

Another reason to be worried is that Europe faces not one crisis, but several. The first is economic: not just the current reality of slow growth, but the prospect that slow growth will continue without respite, owing above all to policies that often discourage businesses from investing and hiring. The rise of populist political parties of both the left and the right across the continent attests to popular frustrations and fears.

Making matters worse for Europe’s economy was the decision taken decades back to introduce a common currency without a common fiscal policy. Discipline disappeared at the national level in many countries; Greece was the most recent casualty, but it is unlikely to be the last.

The second crisis results from Russian actions in Ukraine. There is no prospect of Russia giving up Crimea, and questions about its intentions in eastern Ukraine and the Baltics are mounting. The result is the return of geopolitics to Europe at a time when defense spending is modest and public support for armed intervention is largely absent.

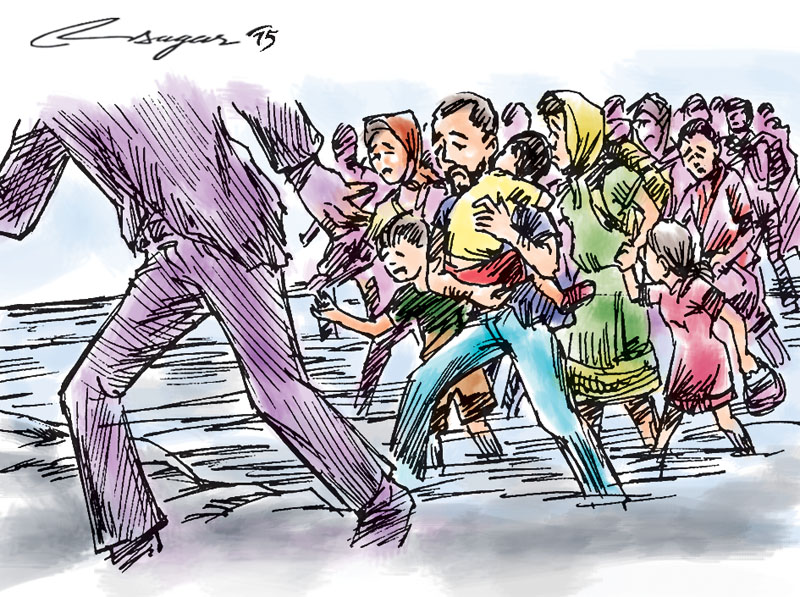

The third, and most pressing, crisis is the result of massive flows of migrants from the Middle East and elsewhere into Europe. The flood of people is exposing new rifts among EU members, raising questions about the principle of open borders and free movement that has long been at the core of the EU.

Germany and a few other countries have stepped up to the challenge in ways that are admirable but unsustainable. Some 8,000 refugees a day – a modern day Volkerwanderung – are entering Germany, partly because of harsh conditions back home, and partly because of Germany’s willingness to take them in. The challenge of caring for, employing, and integrating such numbers will soon run up against the limits of physical capacity, financial resources, and public tolerance.

It is obvious that public policy cannot succeed if it is focused on the consequences, rather than the causes, of the refugee crisis. The change that would have the greatest positive impact would be the emergence of a new government in Damascus that was acceptable to the bulk of the Syrian people and a satisfactory partner for the United States and Europe. Unfortunately, this seems likely to come about only with the blessing of Russia and Iran, both of which appear more inclined to increase their support for President Bashar al-Assad than to work for his removal. Other steps, however, would improve the situation. Increased international financial support for countries in Europe or the Middle East hosting large numbers of refugees is one. Ideally, such funding would help persuade more countries to follow Germany’s example.

Another useful development would be the creation of enclaves inside Syria where people could gather with some expectation of security. Such enclaves would require local support from Kurdish forces or select Arab tribes, with military backing by the US and others.

A new comprehensive arrangement with Turkey is also needed to reduce the flow of jihadist recruits to Syria and the number of refugees heading north. Turkey would receive financial and military assistance in exchange for asserting greater control over its borders, while the question of Turkey’s long-term relationship with Europe would be set aside until the crisis passed.

The US has a special obligation to help. Both by what it has done and what it has failed to do in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere in the Middle East, American foreign policy bears more than a little responsibility for outcomes that have led to the refugee exodus.

The US also has a strategic interest in helping Germany and Europe contend with this crisis. Europe still constitutes a quarter of the world’s economy and remains one of America’s principal geopolitical partners. A Europe overwhelmed by a demographic challenge, in addition to its economic and security challenges, would be neither able nor willing to be an effective ally.

In all of this, time is of the essence. Europe – and Germany in particular – cannot sustain the status quo. Waiting for a solution to the Syrian situation is no answer; while lesser steps will not resolve Europe’s predicament, they could make it manageable.

Haass is president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

© Project Syndicate, 2015.www.project-syndicate.org