Medical education: Not in the pink of health

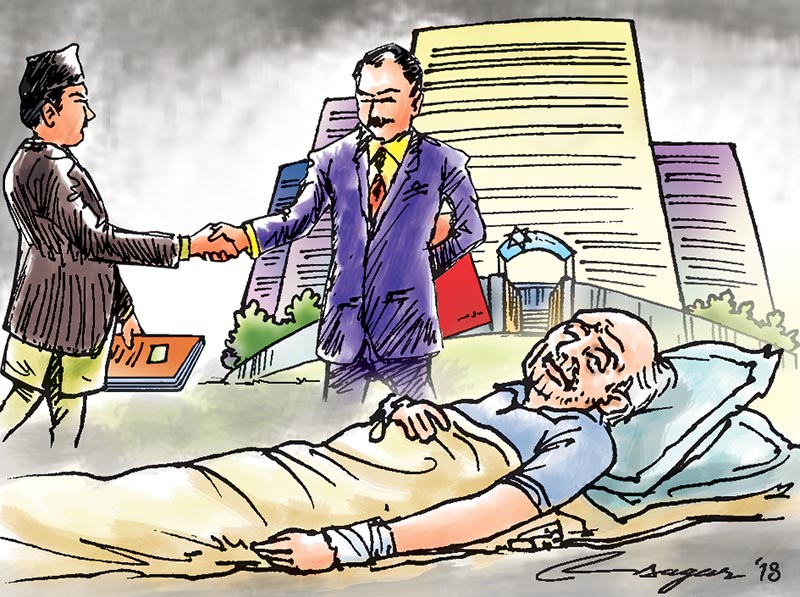

The National Medical Education Ordinance which was introduced following a series of hunger strikes by Dr KC had prescribed three key provisions to improve medical education sector, but government in the replacement bill removed them

Dr Govinda KC’s fight for medical education reforms stems from one basic principle – that quality health care and health care education should be affordable and accessible to everyone regardless of their economic status.

The injudicious opening of dozens of private capitation fee medical colleges in the last decade has resulted in the rampant commercialisation of medical education. They also served as back door entry for the academically less deserving in the medical field, degrading its quality.

The tuition fee amounting to millions of rupees meant only the rich could access health care education. When doctors emerge from this system, their first objective is recouping the money spent on their education, leading to further commercialisation of the field. Interestingly, these colleges enjoy strong political patronage, making their regulations almost impossible.

It was only after Dr KC’s resistance that there were some course corrections, but they were not adequate.

Comprehensive medical education reform will require the government to regulate existing private medical colleges. There is a need to discourage the establishment of new medical colleges as profit institutes. For this, the government needs to increase investment and ownership of people’s health by operating medical colleges like the Institute of Medicine (IoM) that provide quality medical education at affordable costs across the country.

In this context, a team of experts led by Kedar Bhakta Mathema in its report had put forward some recommendations. Based on these recommendations, the National Medical Education Ordinance introduced. Banning new medical colleges in the Kathmandu Valley for 10 years, limiting affiliation to five medical colleges for each university, and hospitals requiring three years of operation to qualify for affiliation were the three important pillars of the bill. But when the government registered the replacement bill in Parliament, it removed these three key provisions to benefit a handful of interest groups. This has defeated the whole purpose of education reforms.

Hence Dr KC’s yet another round of hunger strike — 15th in the last six years —in Jumla.

No medical colleges in Kathmandu for 10 years would have meant no affiliation to Manmohan Memorial Institute of Medical Sciences, Mediciti Hospital and Kathmandu National Medical College. But this provision has been removed. The intention here is ensuring affiliation to some medical colleges and hospitals, which are operated by people who bear a close association with the ruling party.

Of the 20 medical colleges in the country that offer undergraduate and postgraduate medical courses, nine are in Kathmandu. Patients are the most important source of knowledge for a medical student.

As the patients are divided among these institutes, the majority of private colleges haven’t been able to ensure adequate patient flow. Most of them have bed occupancy of less than 30 per cent. During the annual inspection by Nepal Medical Council, these colleges have been found to have “created” patients to show 60 per cent bed occupancy. And, medical colleges outside the Valley lack tutors for basic sciences. They hire Kathmandu-based teachers on contract to complete the courses. More medical colleges in Kathmandu will only make the situations worse.

New medical colleges in Kathmandu will result in a concentration of senior doctors in the Valley, which will deprive MBBS graduates working in rural areas of their opportunity to learn. This will discourage the MBBS graduates from serving in rural areas. As a result, rural people will be deprived of medical care.

Let’s look at the rationale behind affiliation to only five medical colleges per university now. There are nine medical colleges affiliated to Tribhuvan University and seven to Kathmandu University. If this provision is retained, B&C Medical College will not get affiliation to run the MBBS course. The government hence has removed the provision. This clearly shows the intent to serve a few interest groups. The TU and KU are understaffed and underequipped to handle new affiliations. This is why the five-and-a-half-year MBBS course is taking six-seven years to complete. A high number of medical colleges under one university will also mean poor monitoring, which will support commercialisation and profiteering.

Private colleges have been charging students Rs 15-30 lakhs in addition to the Rs 38 lakh fee set by the government. These fees have been deemed unnecessary by the IoM several times.

Thirdly, the provision that medical colleges must run hospitals for at least three years to qualify for affiliation is aimed at ensuring that medical colleges do not charge money to students for the upkeep of the facility and clinical staff. Hospitals that cannot operate without millions in fees from students are in fact failed hospitals and cannot qualify for medical colleges.

Medical colleges are not factories to produce doctors. They are an integral part nation’s health care delivery system. They are supposed to work as health policy think tanks and guide medical education in health care centres all across the country. Private colleges have utterly failed in this regard.

Upreti is medical officer at Charikot PHCC