Population and development in Nepal amid COVID-19

Kathmandu, May 17

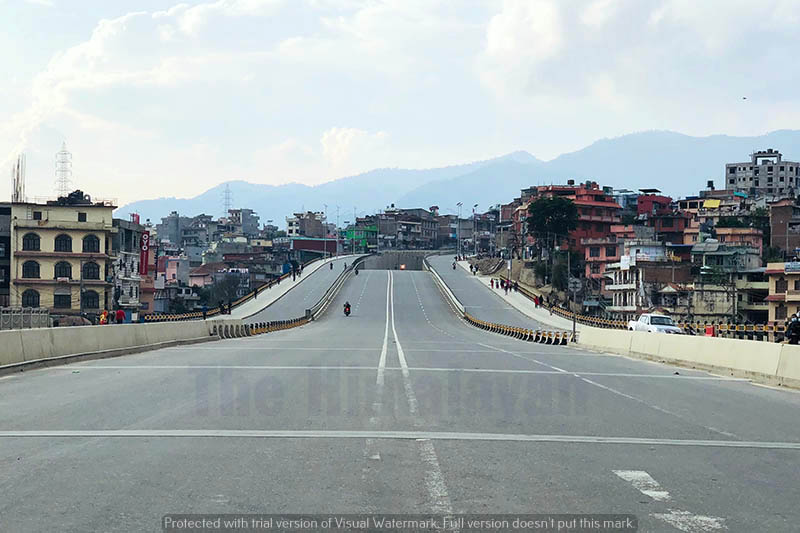

Nepal has adopted a series of measures recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, which includes a lockdown since March 24, when there were just two confirmed cases. But by May 16, the figure has surged to 291 with one death. The detection of COVID-19 cases is proportionately the lowest in Nepal compared to other SAARC countries, although the numbers are fast increasing.

When Nepal imposed a lockdown, many Asian, European and North American countries had also introduced it. The lockdown at home and elsewhere prompted many Nepali working or studying elsewhere to return home. Many of them were put in quarantine and tested for coronavirus infection. If only about half of the immigrant Nepalis have returned, the de facto population of Nepal would now be about 31.5 million, implying an average annual growth rate of 2.16 per cent. The population would grow because of the returnee migrants and relatively high fertility as contraceptives are in short supply, and chances of women getting pregnant are high during the lockdown.

After China, the coronavirus rampage first hit Italy, followed by Spain, the USA, France and Britain, and it gradually spread to nearly all countries of the world. In a matter of two months, these five countries have nearly reached the plateau, and now the incidence is slowly declining after taking a high toll of human lives. Their experience has grave concern for all countries, especially the resource poor ones.

Rough estimates of reported confirmed cases of COVID-19 and the number of deaths attributed to the infection ring an alarming bell to the rest of the world. If these rates are applied to Nepal's population, there should be more than 90,000 confirmed coronavirus cases and about 3,000 deaths attributable to COVID-19.

WHO's recommendation is test, test, test. Without testing, the curve of infection cannot come down. The task is to interrupt the transmission of the virus by conducting testing of the population to find out the incidence of COVID-19 infection in the people. Although testing is tricky, it must be conducted on a massive scale and as speedily as possible. The testing capacity must be upgraded, and it must be extensively distributed in the country, only then can the country gauge the impact of the disease.

How and when the country will get back to normalcy depend on the steps that are taken to contain the disease. The more strictly and correctly the WHO recommendations are followed, the earlier the country can beat the disease and gain normalcy.

Nepal did manage to introduce the lockdown early, but it was not able to upgrade the capacity of the health system for massive testing. As a result, even after nearly one and half months of lockdown, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 is negligible. However, the virus is present in the Nepali masses, and it is likely to grow exponentially because transmission is high from returnee migrants, social distancing is not strictly maintained, and other hygiene practices are not well practised. Besides even if the masses understand the value of following the guidelines due to poverty, washing hands with soap and covering their face with good quality masks are a far cry.

The Nepali economy, which survived the 2015 earthquake and economic sanctions by India, attained only 0.2% GDP growth in 2015/16. And just as it is bouncing back, the COVID-19 pandemic will drag the economy to a bleak future for some years to come. So the development priorities have to be altered, and investments on health and education need to be more than doubled to address the jitters created by the corona pandemic.

The structure of the Nepali economy has changed in the last 50 years. Contribution of the agricultural sector to GDP has declined from 68 per cent in 1971 to 27 per cent in 2019. Contribution of the social sector has increased by nearly threefold between 1971 (22%) and 2019 (58%), and jobs can be created in this sector.

The government will have to slash the regular expenditure in the budget. The analysis of the budgets of the last 30 years shows that regular expenditure was the highest at 64 per cent in 2018/19 and second highest in 2019/20 at 62 per cent. This means the federal structure has been unproductive and costly, which cannot go on unless it is modified. Too many types of perks are lavishly distributed to the elected or nominated bodies, which are not affordable any more at the cost of the poor masses.

Policies and strategies are called for to make the best use of the current labour force (nearly 60% of the total population belong to the 15-64 working age), including the returnee migrants. Programmes like education for income generation for the returnee migrants as well as working age population would pay off enormously. This is the time to reap the demographic dividend, and time is slipping fast.

Unlike the Spanish flu which wiped away millions of people and disappeared, COVID-19, as pointed out by public health experts, will remain with us. Until some form of treatment or vaccine is developed to contain the virus, human sufferings in all their forms will continue. An intermittent and selective lockdown and a mid-way path of preventing the spread of the virus and carrying out of day-to-day economic activities have to be worked out to save the country from falling back. This calls for judicious thinking on the part of policymakers and planners. Only good talking will not work; strict and tough implementation of policies and programmes is called for to get on top of the disease and save the economy from derailing.

Dr Yagya Karki is demographer and former member of National Planning Commission