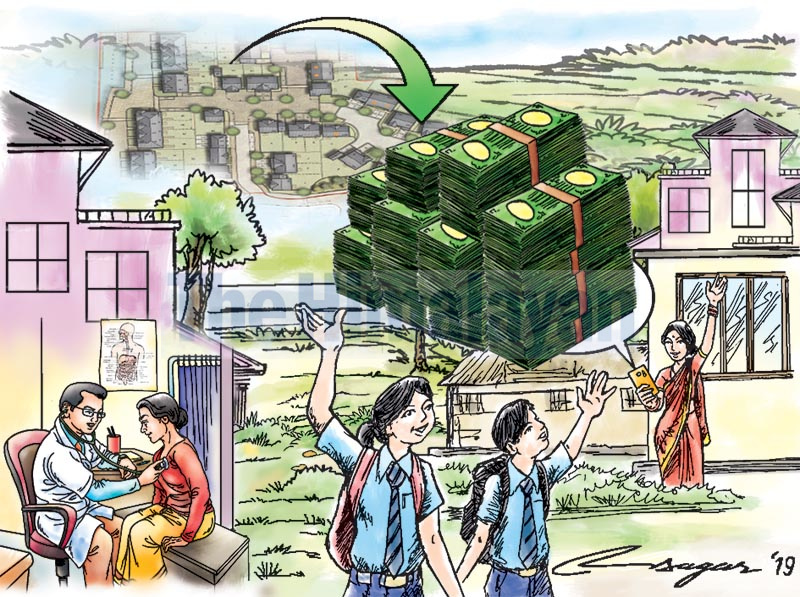

Remittance inflows: Benefits outweigh costs

A large chunk of the remittance-related investment has also raised the stock of wealth of the migrant household in the form of land and housing, all of which have indirect macro-economic impacts on development

Migrant remittances are a long-standing issue in the migration debate. And yet, it has become a focus of increasing attention in recent years owing to the sharply rising flows of remittances into developing countries. According to the World Bank’s Migration and Development Brief released in April 2019, money transfers from migrant workers to poor and developing countries amounted to about $529 billion in 2018, a rise of 9.6 per cent from 2017.

Another reason for the priority accorded to remittances is because they are less volatile than foreign direct investment and portfolio flows. Remittances also act as a buffer against instability at the macroeconomic level. Again in periods of political instability or natural disaster, remittances normally increase as the rising needs of family members cause migrants to send more money back home. Likewise, these financial flows have the potential to contribute to the alleviation of poverty. Further, they have a constructive impact on financial development, including increasing the access and use of financial intermediaries, such as banks, especially in the rural areas. Moreover, multilateral stakeholders view remittances as a source of revenue to be harnessed for development purposes.

In Nepal also, the positive impact of remittances is indisputable. These inflows often comprise relatively small amounts in themselves but denote a lifeline for the recipients.

They are an important part of the financial landscape for the country and have become an important source of purchasing power and foreign exchange.

They have also been instrumental in alleviating poverty as well as generally having a positive impact in the balance of payments; yet, the real economic benefits of remittances have not yet fully materialized.

In FY 1995/96 about one in four Nepali households received some type of remittances.

This figure rose to one in three by FY 2003/04 and greater than one in two by FY 2010/11.

Together with households starting to receive more remittances, the amount of remittances received also soared over the years. The first half of the 2000s witnessed a sharp rise in remittances from 2 per cent of GDP in FY 1999/2000 to 15 per cent in FY 2004/05, 22 per cent in 2009/10 and 25 per cent in 2017/18.

Recently, workers’ remittances soared by 20.9 per cent to Rs.553.19 billion in the first three quarters of 2018/19 compared to a growth of 5.6 per cent in the same period a year ago. In US dollar terms, these inflows increased by 9.5 per cent in comparison to the rise by 9.6 per cent in the corresponding period of the previous year. The sharp increase came despite declining outflows of migrant workers by 39.3 per cent in the first three quarters of 2018/19 compared to the same period of the previous year.

The upsurge in these financial flows can be ascribed to policy actions in destination countries. Malaysia, for instance, shut down a few agencies that process visas for Nepali migrant workers owing to worries about overcharging migrant workers. In the Gulf countries, fiscal pressures resulted in expenditure cuts that adversely impacted the demand for migrant workers. Again, labour market “nationalisation” policies in the GCC countries also put off the hiring of foreign workers. In this perspective, the higher remittance flows into the country could be ascribed to the depreciation of the Nepali rupee against the US dollar.

Nepal’s budget for FY 2019/2020 and the Monetary Policy for 2018/19 have accorded priority in directing remittances through the banking system as well as mobilising remittances towards productive use (such as micro and small industries, agricultural enterprise and employment-oriented services).

These issues were also given attention in the previous budgets and monetary policies.

Unless the government takes concrete steps in implementing these policies, no tangible results will emerge.

Studies on Nepal’s remittance inflows show that a large portion is used to finance consumption rather than being directed to raise the productive capacity. It should be understood, however, that spending remittances on consumption generally results in improved health, education and human capital, increasing both private and public welfare. Likewise, a large chunk of the remittance-related investment has also raised the stock of wealth of the migrant household in the form of land and housing, all of which have indirect macro-economic impacts on development.

However, there are concerns that the positive effects of these transfers can get reduced when individuals are overly dependent on them. There are macroeconomic fears pertaining to remittances as they can contribute to currency appreciation and could also adversely impact labour supply since remittance-recipient households may opt for more leisure than labour. Too much dependence on remittances also exposes Nepal to external shocks. And, excessive reliance can produce a dangerous dependency that may impede longterm productive economic growth.

Despite these fears, the positive impacts of remittances have outweighed the adverse impacts, and these inflows should be further encouraged with appropriate and persuasive policies by the government.

Pant writes on globalisation and trade issues