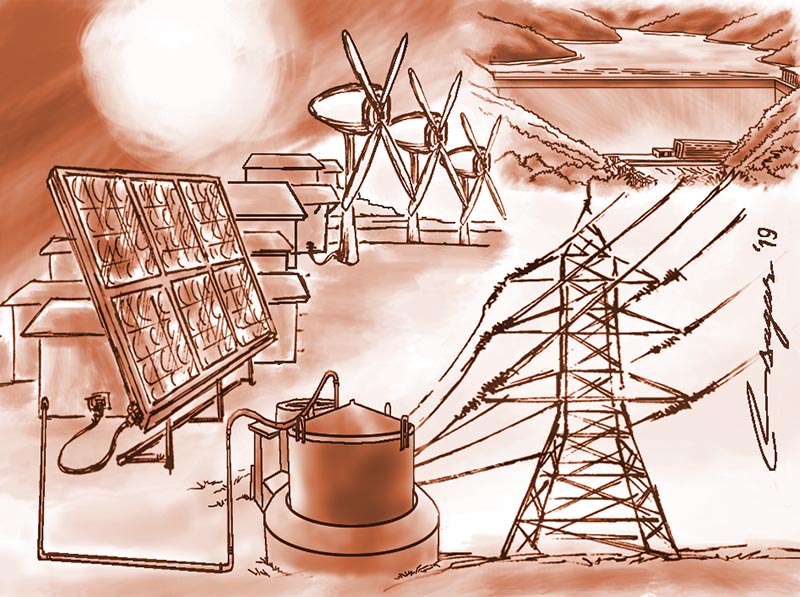

RE financing: Need for paradigm shift

The major thrust now should be on strengthening and enhancing the capacity of the provincial and local governments to plan and deliver the finance effectively in the renewable energy sector, considering their specific development needs

Nepal has a long history of renewable energy (RE) financing, dates back to 1968. The Agriculture Development Bank of Nepal (ADBN) was providing credit and channelling government subsidies to RE technologies, mainly micro-hydropower, biogas and solar systems. Bank credit mixed with the government subsidy made the RE sector very attractive for the private sector service providers and rural people.

So far, RE financing has been guided by policy provisions of the government and institutional setup, mainly the Alternative Energy Promotion Centre (AEPC) and later the banking sectors organised under the Central Rural Energy Fund (CREF). Additionally, some funds are also channelled to the RE sector outside the AEPC financing framework.

The Subsidy Policy and Subsidy Delivery Mechanism were promulgated for the first time in 2000. These two documents were amended from time to time, and the latest versions were made available in May 2016 and November 2016 respectively. AEPC instituted the CREF to channel the subsidy and credit funds to promote RE activities in 2013.

The Subsidy Policy recognises that the past subsidy could not effectively mobilise private investment or commercial credit into Nepal’s RE sector. Rather dependency on subsidy has increased. It was inferred in the policy document that communities were striving to get subsidies from multiple sources. One of the reasons for it was related to energy tariffs in rural areas, which were not sufficient to recover the initial investment costs of the system. But this was not the only reason.

The latest subsidy policy (2016) focusses on replacing subsidies with credit in the long run and achieving universal access to clean, reliable and affordable RE solutions by 2030.

The key determinants of subsidy are based on (i) remoteness and geographical region, (ii) subsidy, credit and equity ratio – generally 40%, 30% and 30% respectively, (iii) cost competitiveness (least cost) and (iv) social, economic and technological appropriateness (best available technology). Based on these criteria, the policy has come up with the subsidy amounts to be given for different technologies, such as mini/micro-hydropower, improved water mill, solar energy, biomass including biogas, wind energy and the like.

On top of this, a provision of additional subsidy has also been made for some technologies, such as mini/micro-hydropower. Additional subsidy is allocated to the targeted beneficiary groups by counting the number of households which are served by the project.

The subsidy policy provides equal thrust to mobilising credit, at least 30%.

Some of the government programmes are targeted towards specific groups, such as earthquake victims and ultra-poor. Some programmes address the market areas and can have a commercial operation, such as urban solar and streetlight, and irrigation. Subsequently, some of these programmes can be executed without subsidy at all or a little subsidy based on innovative financing provisions. For some programmes, especially targeting special groups, such as ultra-poor and remotely-located settlements, the traditional subsidy cannot be completely ruled out.

Apart from these, AEPC has received a grant from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to implement the South Asia Sub-regional Economic Cooperation (SASEC) Power System Expansion Project. The off-grid component of SASEC intends to increase access to renewable energy for improving the livelihoods of the people and creating employment opportunities, especially in rural areas. The project is consistent with the ADB Country Partnership Strategy.

For the project, there is a provision of a credit line of $5 million from the ADB’s Special Funds to user communities/developers for mini-hydropower plants and $11.2 million grant from the Strategic Climate Fund (SCF) administered by the ADB.

The Scaling-up Renewable Energy Programme (SREP) is supporting the Extended Biogas Project. It aims to promote large off-grid biogas energy generation in Nepal through technical assistance and financing of investments (partial capital cost buy-down of biogas sub-projects though subsidy payment).

Financial flow mechanisms for these programmes are based on the bilateral agreement between the Government of Nepal and the respective funding organisation.

Though AEPC aims to promote a single programme modality, there still exist multiple programme modalities and financial flows. In such a context, a flexible framework, which can accommodate all development partners and government money flow, is needed.

In the present context of federal set up, these approaches need to be aligned considering the mandates of the provincial and local governments that have a major stake in developing renewable energy. There is a need for a new modality that is compatible with the federal, provincial and local governments. The major thrust now should be on strengthening and enhancing the capacity of the provincial and local governments to plan and deliver the finance effectively in the RE sector, considering their specific development needs.

Adhikari is an energy economist