Theory of evolution: Diversity of nature makes sense

The main idea of evolution lies in the transfer of a gene for a particular trait over multiple generations, which makes it impossible to see such events live in front of our eyes in real time

The theory of evolution is overshadowed by various misconceptions, making it one of the most controversial among various scientific theories. Scientists and philosophers have wondered about the vast diversity of plants and animals around us since the beginning of human understanding. But it took one scientist to connect the dots. It was Charles Robert Darwin, born 211 years before on this day, who took a daunting voyage to South America and the surrounding islands, especially the Galapagos, on the HMS Beagle and changed the course of human understanding. It was in those islands that the poetry of evolutionary history unfolded in Darwin’s mind.

But before getting into what Darwinism is, I will lay out some ideas about evolution. It is a gradual change in different characteristics of a species over a long period of time. One question that you constantly face is, why can’t we see evolution happening in front of us? The answer to that is, we can.

Now what is Darwinism? The key component of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution is Natural Selection. Put simply, evolution by natural selection is the process whereby the “fittest” survive and reproduce while the unfit ones die out. The idea of evolution by natural selection was not well received during Darwin’s time, neither did it cope well after his death. But at the peak of the industrial revolution, something happened that helped Darwin’s idea of evolution to resurface on the scientific world.

A lighter colour version of a moth called the Peppered Moth (Biston betularia) was prominent in the area before the onset of the industrial revolution. The moths used the white lichens on the barks of trees for shelter and camouflage. But with increasing air pollution, the lichens died, and exposed the white moth against the dark background of the tree. Shortly after the plunge in the white moth’s population, a darker version of moth, black peppered moth started appearing in the area. Almost 98% of the moths were black in 1895. The white peppered moths on the dark background on the tree bark were easy prey for the birds, and hence, they weren’t “fit” for that particular habitat. Later on when the pollution decreased in the area, the white peppered moth resurfaced again.

There are numerous examples of such selection happening in nature and among us. During Darwin’s voyage to the Galapagos, he saw different finches that looked similar but had different beaks. He collected tons of specimens of the birds and took them back to England. Upon further inspection and investigation, he realised that all of those birds came from a common ancestor from the mainland or island. Depending upon what they were feeding on, they needed a special type of beak.

One more example. There’s a fish called the Mexican blind fish, which doesn’t have eyes anymore. It used to, but then the fish started living in dark caves, which meant they were better off without eyes. Since investment in vision demands a lot of energy, in places with less amount of food that could be very costly. And yes, there is a member of the same fish family that lives in a river, which still has eyes.

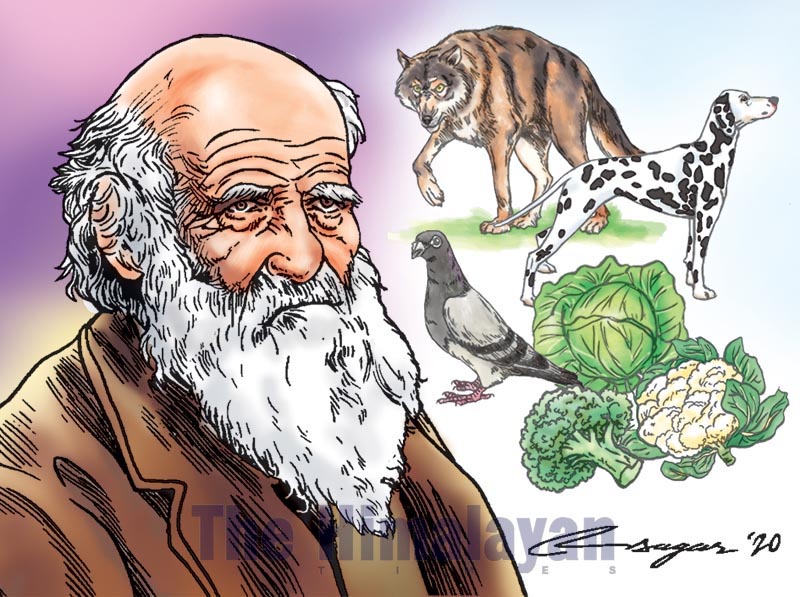

The “getting out of the species” portion takes a long time. That means speciation or formation of a completely new species, which seems far-fetched, but that’s how we have all the diversity of animals. You might have seen different types of pigeons, almost all of them came from the Rock pigeon that we see around Basantapur. How about this? Cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, kale and brussels sprouts all came from a wild variety of mustard. Over a longer period of time, people bred for specific traits and ended up with varieties of plants, all of which tie back to the wild mustard plant (Brassica oleracea). Or look at dogs, bred from a category of wolf to modern day dogs, from Huskies (similar looking to wolves) to the Dachshund, which looks nothing like a wolf or any dog of a bigger breed.

This is a case of artificial selection by us humans, in a similar way nature selects for traits and ends up producing different types of animals in the long term. With the plant and dog example, the question about not observing evolution happening in real time should have been partly answered by now.

The main idea of evolution lies in the transfer of a gene for a particular trait over multiple generations, which makes it impossible to see such events live in front of our eyes in real time. But if you’ve ever been asked by your doctor to complete the antibiotic dose, it is because of evolution. The reason is, if you start an antibiotic, which obviously doesn’t kill all the bacteria at once, and by stopping the dose, you’d assist them to evolve into a resistant version of bacteria, which means you’d have to get a stronger version of antibiotic, and at a point you’d run out of choices. It’s easier to see evolution happening in microbes because of the rapid reproduction cycle.

It’s not just the microbes though, there are faster evolving vertebrates, too. Some species of lizards are losing their legs at a very fast rate (in only 15 years). If they continue to lose the legs at that rate, what would they look like? So, I guess the evolution of snakes from lizards doesn’t sound too cryptic now? Similarly, the evolution of a bird from the dinosaur should feel normal, too. Evolution does make sense, doesn’t it?

Ghimire is a PhD student at North Dakota State University