Women deliver: Let them handle GBV

Although the mere presence of women in political positions does not guarantee any particular policy outcome, their greater representation in the legislature is linked to increased legislative focus on health and other social services

The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence (GBV), an annual international campaign, came to an end on December 10. Amid the campaign, the world has witnessed many cases of GBV. Priyanka Reddy, a 26-year-old veterinary doctor in Hyderabad, India was gang raped and murdered, which sparked outrage across India and even the world. Similarly in Nepal, Parwati Budha Rawat was found dead while staying in a “menstruation hut” in Achham district, Sudurpaschim Province. Likewise, a few months ago, Aarti Chaudhary, had filed a complaint at the District Police Office in Dhanusha after her husband, Indrajit, and in-laws physically abused her for failing to bring enough dowry.

One question regarding this issue is, why did the girl’s side not file a complaint against Indrajit when dowry was demanded in the initial phase? When someone files a case against demand for ‘enough dowry’, does it not indicate that dowry is legal? Dowry is related to the mindset of the people and is an anti-social practice.

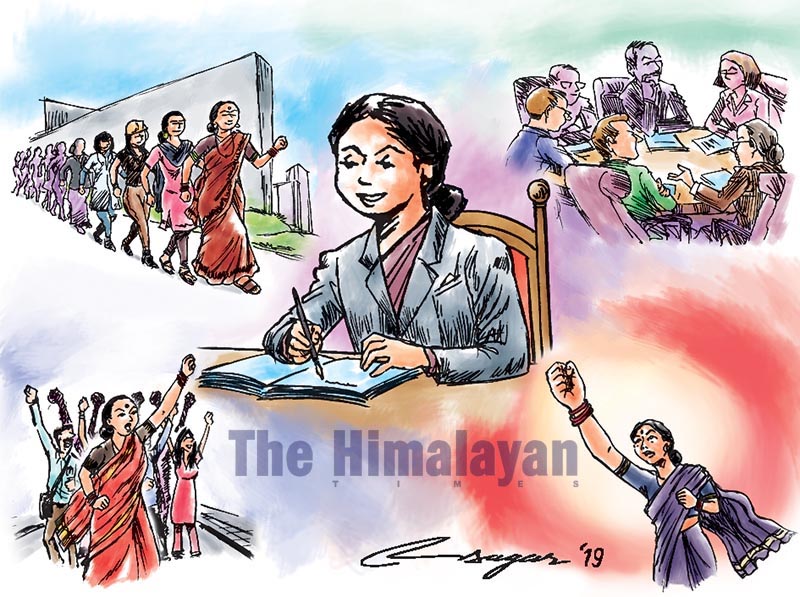

The above incidents of GBV are only representative cases. However, violence against women is being endured even in the 21st century. Despite the feminist movement, GBV exists in Nepal and throughout the globe. In Nepal, in particular, such a scenario is related to the level of women’s empowerment and their level of domination in leadership positions. Since women’s presence in the state apparatuses is very low, GBV cases are not being handled aggressively.

There had been a political deadlock in Nepal for decades. After completion of three elections and the constitutional obligation in the aftermath in favour of gender and social inclusion, the political impasse has ended. Full participation of women in political life is not only a guarantee of their human rights, but also an essential requirement in building peaceful societies. The veteran human rights activist, Michelle Bachelet, once said, “When one woman is a leader, it changes her. When more women are leaders, it changes politics and policies.”

Regarding the status of Nepali women’s representation, there is a need to shed some light on it. Nepali women’s representation in the legislative body was dramatically increased to 32.8 per cent through the Constituent Assembly (CA) election held in 2008. In the election, 191 women leaders (33.2 per cent) were elected out of 575 seats, and the Cabinet nominated six women out of 26 seats, resulting in 197 women members (32.8 per cent) in the legislative parliament. As a result, Nepal stands 14th globally in sending women leaders to the legislature parliament. The reason behind the dramatic change in women’s representation is the reservation of seats provided through the Interim Constitution of Nepal, 2007. This gradual constitutional obligation also gave the first woman president in Nepal.

With the first woman president, there is some hope that people will see positive change in terms of empowering women through education and developing their leadership capacity. Beyond its intrinsic value, greater gender equality in politics and public life will bring distinct orientations and behaviours to office. Indeed, among citizens and legislators, women and men often have different political interests and priorities, issue positions, party preferences and legislative behaviours. Although the mere presence of women in political positions does not guarantee any particular policy outcome, their greater representation in the legislature has been linked to increased legislative focus on health and family policy, more spending on social services and less on defense.

Currently the Federal Parliament has 32.7 per cent women. But very few women are seen vocal in raising concerns on national issues with rationality. So they need to be provided leadership training to sharpen their capacity. If we look at the political parties, constitutionally, all four parties—the Nepal Communist Party, Nepali Congress, Samajwadi Party Nepal and Rastriya Janta Party Nepal—are illegitimate in that they have failed to ensure the constitutionally-mandated minimum 33 per cent of women in the party structures. The status of women in the Nepali bureaucracy is just as pathetic.

In Nepal, due to the constitutional obligations, women have been able to hold political positions as mere representatives. But there is a vast difference between representation and leadership. The time has come to think why the representatives cannot be ‘leaders’. The feminist critique of patriarchy is founded on the arguments that all social structures and systems, and all political systems, are patriarchal. According to feminist arguments, the division of power between men and women that has persisted throughout human history systematically oppresses and disadvantages women. It operates throughout society, in politics, work, the family, legal and judicial systems.

Last but not the least, women should be posted at law enforcing positions. There is a need to eliminate the patriarchal mindset from society, only after which a level of change will be seen in the society. The anti dowry and chhaupadi law must be implemented brutally to discourage such anti-social practices.

Chaudhary is Member of Parliament & General Secretary of RJP-Nepal