Zelaya issues ultimatum

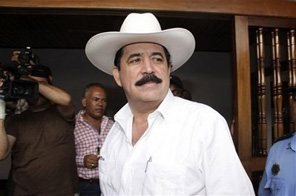

TEGUCIGALPA: Ousted President Manuel Zelaya, clearly frustrated with stalled negotiations aimed at resolving the country's political crisis, issued an ultimatum to the interim government Monday: Reinstate me or else.

Zelaya delivered his message at a news conference in Nicaragua, where he arrived Sunday night following a brief trip to Washington.

At the same time, the de facto government installed by leaders of the coup that forcibly exiled Zelaya on June 28 tried to return life to normal, successfully urging tens of thousands of Honduran teachers and students to return to class Monday.

Interim President Roberto Micheletti said a Honduran negotiating team could return to the bargaining table as early as this weekend to try to end the stalemate caused by the coup. Two previous rounds of talks mediated by Costa Rican President Oscar Arias failed to produce a deal.

At the swearing-in ceremony of a new foreign minister Monday, Micheletti said his team of delegates was "ready for another meeting."

But Zelaya said Monday that he was "giving the coup an ultimatum."

If the interim government does not agree to reinstate him at the next round of negotiations, he said, "the mediation effort will be considered failed and other measures will be taken." He did not specify what actions he might take.

Zelaya accused the Micheletti government of "using" the talks "as a means to distract attention," and said the interim regime had "systematically increased repression" against demonstrators, journalists and others.

Members of Micheletti's administration did not immediately respond to Zelaya's comments.

Arias, the 1987 Nobel Peace Prize winner for his role in helping end Central America's civil wars, was expected to announce the date for new talks on Monday, said a Costa Rican government official, who was not authorized to give his name.

In Washington, State Department spokesman Ian Kelly reiterated U.S. support for Arias' mediation efforts.

"It is not a process that's being led by the United States of America. We just have to give time for this process to work. And I'll just say, we're standing firmly behind President Arias," Kelly said.

Despite Kelly's comments, Washington has clearly been playing an influential role in the negotiations: It was U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton who invited Arias to mediate and Zelaya supporters have been urging the United States in particular to take firm action that they say would force the interim government to back down.

The coup has drawn international condemnation and nations have urged that Zelaya be restored to his post as the democratically elected president.

Honduras' Supreme Court, Congress and military say they legally removed Zelaya for violating the constitution. They accuse him of trying to extend his time in office, but Zelaya denies that.

Both Zelaya and Micheletti, the congressional president who was appointed by lawmakers to serve out the final six months of Zelaya's presidential term, met separately with Arias last week but they refused to talk face to face.

Former Honduran Foreign Minister Carlos Lopez, a Micheletti representative at the talks, said his side had not ruled out the possibility of early elections as a way out of the crisis.

As the crisis drags on, the interim government has urged people to resume their lives as usual in Honduras. About 38,000 teachers heeded a request to return to class Monday — but more than 20,000 remained on strike to protest the coup.

High school director Alejandro Ventura said that thousands of teachers decided to go back to school because there is no solution in sight for the political crisis. "We cannot keep acting irresponsibly with our children," he said.

Most of the children affected by the walkout also returned to class, said teacher's union leader Eulogio Chavez.

Zelaya supporters have said the interim government is trying to restore normality to the nation with the hope of sapping the energy of the protest movement and staying in power until the November presidential election.

Daily demonstrations for and against the forcibly exiled Zelaya continue in the country, but are steadily losing steam. Turnout at demonstrations has fallen from several thousand to only a few hundred this week.

"Each day fewer people come and our leaders are disorganized," said Rosaura Izaguirre, one of about 300 Zelaya supporters blocking a main road connecting the Caribbean coast to the capital for two hours Monday.

Micheletti's administration said Sunday a nighttime curfew that had been in effect for two weeks was no longer needed because it had met its goal of restoring calm and curbing crime.

The new government had ordered Hondurans to stay inside from 11 p.m. to 4:30 a.m. — a restriction that briefly extended from sunset to sunrise when Zelaya tried to return and the military kept his plane from landing by blocking the runway at the capital's airport a week ago.

Early Monday, cars could be seen on the streets once again as people visited bars and vendors and street musicians returned to work downtown.

"During all these days we had problems because we did not work. Our family depends on this work. This is our life," said Fredy Rivera, a musician.