Don’t ban ride-hailing: It is part of the gig economy

Without the ride hailers’ effort, the platform will not generate a single penny. The sweat, time and effort of the rider are the base of the business of the platform economy. This the government must understand

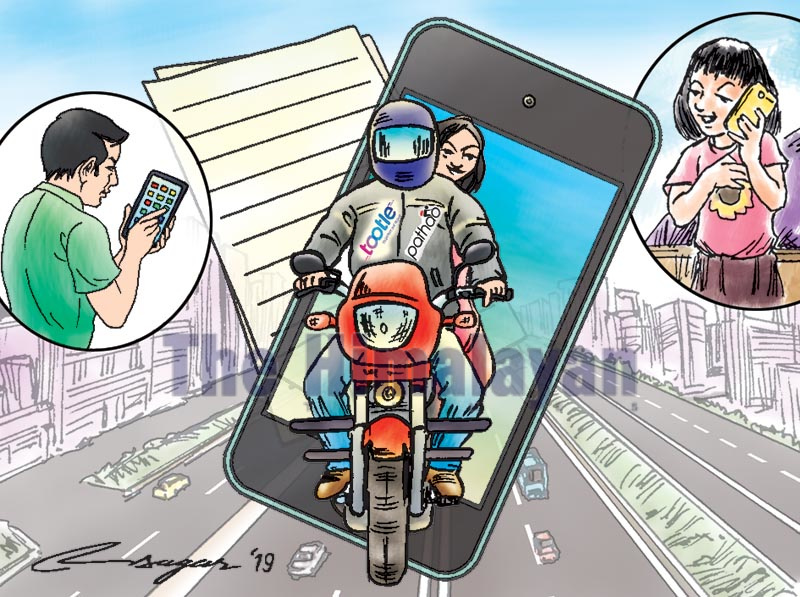

The IT-enabled ride-hailing services have been in discussion and in question for the past few months. The Department of Transport Management says it’s illegal as per the prevailing law of the land. But, is the ban a solution? Shouldn’t the government open a dialogue to be heard by all the stakeholders? Shouldn’t the government understand the aspiration of innovative forces? We must understand that ride-hailing has emerged in Nepal not solely because of the irregularities seen in the conventional taxis, such as overcharges or refusal to give a ride, but is the process of globalization, which is inevitable.

Ride-hailing is not a patent idea of Nepali developers. It originated somewhere else and is already widely practised. In terms of economy, the ride-sharing market is booming, and despite the recent roadblocks, shows no signs of slowing down. JWT Intelligence claims that the global ride-sharing market could be worth more than $170 billion by 2025, from $43 billion in 2017. This growth is making room for new players in ride-hailing around the world, challenging market leaders and expanding the original ride-hailing model into a nimble, omni-channel suite of services.

Tootle or Pathao in Nepal might be a novel digital platform for mobility, but outside the country these IT-enabled services are not new. It is just a technological innovation that fulfills the need gap between the service provider and the customer. To borrow the definition by author Nick Skillicorn, the innovation is “turning an idea into a solution that adds value from a customer’s perspective”. I am pretty sure we definitely will witness many more innovations in the near future.

The purpose of my write-up is to ensure social security for the gig economy, or the platform economy workers, in terms of ride-hailing, which is representing non-standard employment.

Nepal has introduced social security through contributions based on the Social Security Act-2017, which is now in action. Private enterprises have been made to register as employers, and under them, the workers are registered with a social security number. It is a new scheme, and the first of its kind in South Asia as well, which covers the private sector employees in Nepal. The Social Security Fund (SSF) claims that about 30,000 employers are registered in the Social Security Fund as employers while about 110,000 workers are registered.

In the eye of Labour Law-2017 of Nepal, there are no informal workers because the workers are categorised into five employment forms, such as Regular Employment, Work-Based Employment, Time-bound Employment, Casual Employment and Part-time Employment. The law doesn’t recognise another form of employment in this respect. Now the question is, how do we define the ride-hailers? Aren’t they workers? Should we define them as self-employed? In this case, most of the international practices have different approaches to defining and understanding it according to their own context and legal systems. But the main feature is that without the ride hailers’ effort, the platform will not generate a single penny. Therefore, the sweat, time and effort of the rider are the base of the business of the platform economy. The government must understand this hidden fact in the gig economy. The gig economy, which is also called platform economy, refers to the availability of crowd workers. This will equally apply to other IT-enabled services, including e-commerce, online shopping, web/app based goods and service providers.

Hence, the platform economy owner (the platform provider) must be made to register them as employers with the Social Security Fund, then only should they be able to operate their business activities, whether IT-enabled or non-IT-enabled. Once the service providers (the platform owners) are registered as employers with the fund, the riders will automatically be registered in the system. According to an estimate, there could be more than 50,000 registered riders in the ride-hailing platform in Nepal, especially under Pathao and Tootle. This must be recognised as a new form of employment under the gig economy. Anything that is linked to economic activities and is operating in the country without any legal system is obviously dangerous and arouses suspicion. So we need a system to regulate the ride-sharing services in the gig economy.

With the ride-sharing industry to grow at a rate of more than 20% during 2019-2025 worldwide, I am optimistic that sooner or later the current issue of the legality of private-vehicle use in the ride-sharing platform, that is, Tootle and Pathao in Nepal, will be resolved, and they will be recognised with some prerequisites and conditions to fulfill. As stated above, there is no doubt that the platform economy is creating jobs for the new generation in Nepal, which is also a focus and prime concern of the government. Out of the many concerns in this scenario, the government’s prime concern must be to include the ride-hailers under the contributory social security of Nepal, which provides monetary assistance to the contributor (worker) with inadequate or no income during the course of employment or at the stage of no employment. The government should be a referee and allow fair play in this new form of future work.

Khadka is pursuing his PhD on Social Security of Nepal at TISS Mumbai