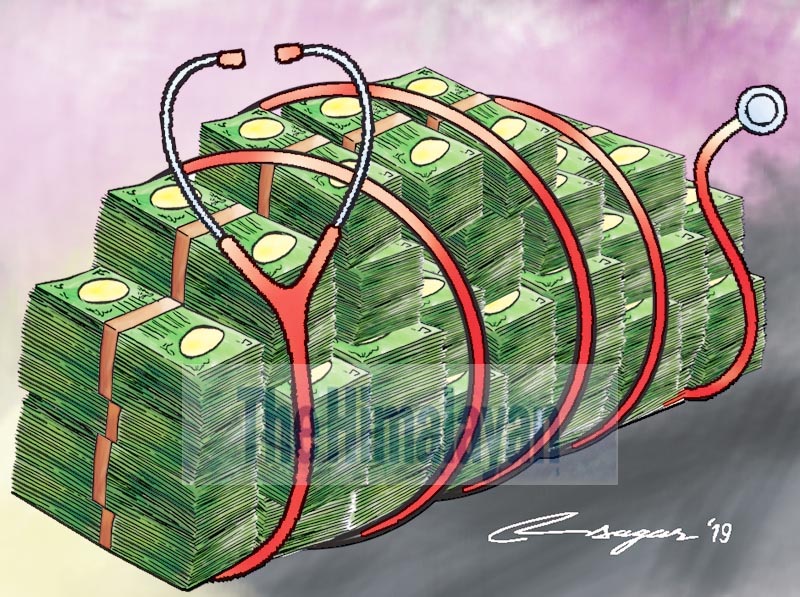

A doctor’s dilemma: Choice between service, commerce

The title of ‘doctor’ is no more a ‘sign of academic success’ as in the past. Medical colleges, once considered to be a ‘future destination’ for a few select and deserving candidates, are now similar to a ‘production-house’ of doctors

February 1, 2005 (Magh 19, 2061), Tuesday, the day we had planned to leave Bhairahawa after passing the final MBBS exams from Universal College of Medical Sciences (UCMS). Due to the political scenario that had developed on that very day, we had to postpone our trip to Kathmandu by a couple of days. However, I can now claim that it has been more than a decade since I have become a doctor.

Plenty of water has flown in the Bagmati since then. From an era when lots of ‘blood, toil, sweat and tears’ were needed to become a doctor to the time when loads of currency are an ‘essential’ to wearing a white coat……so much change.

I still remember my childhood and schooldays when my parents idolised the ‘SLC Board-holders’ and had us dream of becoming ‘a doctor’ citing their example. Seeing the rush of white coats in the hospitals, I would also visualise myself being one of them and pray involuntarily to the unknown. For every so-called position-holding student, in general, and those born-out-of the middle class family like ours, in particular, the scholarship scheme of the Ministry of Education (MoE), or merit list, in a handful of institutes like the Institute of Medicine (IoM) and BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences (BPKIHS) were the only hopes to aspire for. No other chances.

Were it not for the farsightedness of the unknown policy makers who had made it mandatory for the private medical colleges to set aside 20 per cent of the seats for MoE merit-holders, my childhood reverie of wearing a white apron in a hospital would have remained a mere fantasy. How could deals worth millions, currently seen in the medical education system, make a doctor out of us?

Travelling back in the time machine, I remember each and every face of our batch-mates entering the UCMS proudly after being nominated by the MoE 15 years ago. What a coincidence! Similar socio-economic background, analogous family environment and more than a year’s battle in the different entrance examinations - running through the preparation classes, mock exams, different institutes, embassies and much more. Familiar faces meeting again and again. I do not know if the change in the question pattern and interview scheme, and the ‘quota system’ are able to really filter the needy and efficient candidates at present. I am also not sure if a period of 10-15 years is sufficient time to be judgmental in this arena.

Starting on a positive note, I am grateful for the opportunity to do my post-graduation within a year of working as a medical officer. Seeing the current state of affairs, I did not have to face many hurdles, and was able to get through the specialty of my choice. Today it is a different story.

The past decade has witnessed so much change. The Nepal Medical Council (NMC) has its own grand building. There is a licensing examination, not only for the graduates, but also post-graduates. An MD/MS is not enough now, everyone aims for super-specialisation, such as DM/MCh and the like. Nursing homes, polyclinics, state-of-the-art hospitals and medical colleges are budding everywhere. But are these really substantial? Has there been sufficient gain in the quality? How is the valuation of ethics and moral standards vis-à-vis economics and social principles regulated?

I really cannot state whether the ‘academic superiority’ of an individual or the ‘socio-economic excellence’ of one’s family should be the decisive factor in medical education in our country at this stage. The bank balance of at least a crore, or Rs 10 million, is necessary if any parent wants his child to become a doctor. There is no more pressure to study and no need to ‘burn the midnight oil’ for the entrance examination.

The ball of being a doctor is not in the child or student’s court now, it is in the parent’s pocket, whether the student wants to become ‘a doctor’ in the family or not. Ironically though, being a doctor is not a student’s ‘passion’ rather a ‘compulsion’ for the non-students.

One more harsh reality to share! This decade has also seen so many of my colleagues leave the motherland to utilise their hard-earned knowledge and skills and to test their future on foreign soil. I am not sure whether their ‘self’ really wanted it to be like that. But, still, I would like to take a long breath thinking about it.

There are so many questions entering my brain at this phase. The title of ‘doctor’, once considered a ‘sign of academic success’, has turned out to be a ‘parameter for economic accomplishment’. Medical colleges, once considered to be a ‘future destination’ for a few select and deserving candidates, are now similar to a ‘production-house’ of doctors.

However, quite paradoxically, despite the diminishing ‘scholarship plans’ and hike in the ‘fee structure’, there is an overflow of medical doctors in the country. But, are the poor and needy village people getting the minimum health facility? Is the government policy to enable ‘health for all’ efficient? Are the doctors now being seen really the forerunners in the society? And, more importantly, are they really well-settled?

After more than one-and-a-half decades of being a doctor, I am finding everything not easy. Where have the legendary Hippocrates and his oath hidden?

Dr Risal is a psychiatrist at Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University