Post-quake reconstruction: Sustain the achievements

An important lesson learnt is that reconstruction in the aftermath of a major disaster is not just a technical issue. Social, political and financial aspects also govern the process as a whole, and perhaps have more influence

This week, Nepal commemorates the fourth anniversary of the massive 7.8 magnitude Gorkha Earthquake that jolted the country on April 25, 2015. In the subsequent years, the entire country has immersed itself into rebuilding the damaged structures and facilities, with private houses getting the topmost priority. Four years after the disaster, more than half of the identified and listed earthquake-affected beneficiaries have completed construction.

However, the current achievement has constantly been undermined for not being able to satisfy the aspirations of those who were affected for quick and sustainable recovery. So, how is the reconstruction in Nepal taking place? How was the case of other countries that had to face similar devastating situations? What are the identified gaps in our process, and what lessons can we derive from our assiduous efforts in the past four years to be used for dealing with the aftermath of similar disasters in the future?

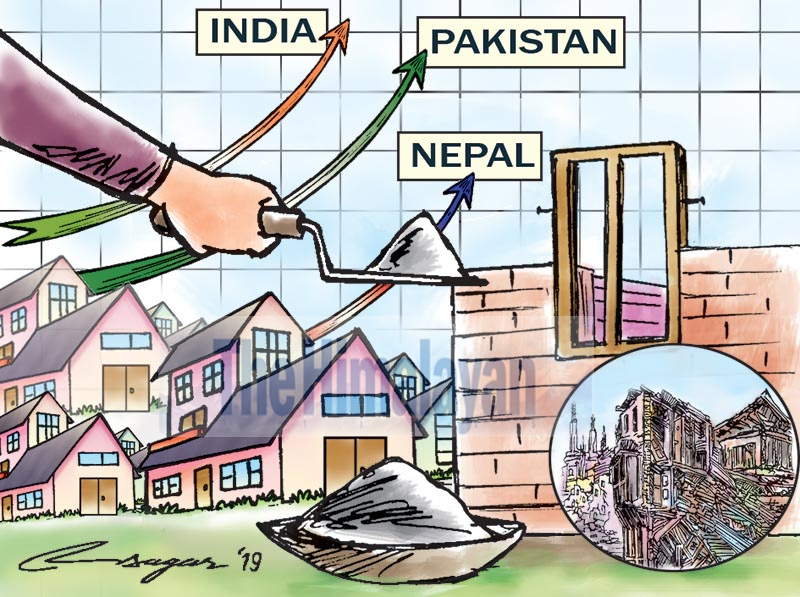

In a recent update, it was reported that 46 per cent of the identified beneficiaries have completed construction, most of them compliant to prescribed standards. Another 28 per cent are currently building and are expected to complete soon. This achievement, in the period of four years, is significantly slower when compared to the progress of post-earthquake reconstruction in the aftermath of the 2001 Bhuj Earthquake in India and the 2005 Kashmir Earthquake in Pakistan. By the fourth year, more than 87 per cent of the buildings were already rebuilt or retrofitted in Gujarat, and more than 70 per cent of buildings were compliant up to the lintel level in Pakistan.

The slow progress in Nepal can be attributed to the delay in the onset of the reconstruction process as a whole, with policy formulation taking up much of the time in the first year of the earthquake. Evidently, the National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) formally came into existence in December 2015, eight months after the earthquake, while similar reconstruction authorities in Gujarat and Kashmir were formed within a month of the disasters. The delay created an undesirable atmosphere of confusion among the beneficiaries, thus deterring beneficiaries to rapidly engage in reconstruction.

In the following three years, however, the reconstruction progress accelerated rapidly, with mobilisation of huge manpower for technical and financial support. Deadlines were announced in the same period to motivate beneficiaries to rebuild faster. Up until April 2017, no beneficiaries had received the second or third tranche of the subsidy. Two years later, 68 per cent and 49 per cent of the beneficiaries have received the second and third tranches, respectively. This number, coupled with the fact that the effective construction period in rural Nepal is only 4-5 months in a year, is overwhelming.

The rapid reconstruction is seen both positively and negatively, with several asserting that the houses built do not meet the needs of the people. In the meantime, however, a large portion of the earthquake-affected beneficiaries have now shifted to a permanent structure and are returning to their normal livelihood activities. An important lesson learnt from this is that reconstruction in the aftermath of a major disaster is not just a technical issue. Social, political and financial aspects also govern the process as a whole, and perhaps have more influence.

Another major challenge seems to be the effective mobilisation of skilled human resources. While the country was reeling under a lack of human resources for reconstruction, several villages were being emptied of youths, engaged as they were in foreign employment. With proper planning, perhaps the nation’s workforce currently toiling under harsh conditions abroad could have been persuaded to work in their own villages. The shortage of manpower could also have been fulfilled by the facilitation of masons from other places.

Despite all these, an Owner Driven Approach was adopted, which in several post-earthquake reconstruction in other developing countries has proved effective and highly acceptable, as it shrinks the cumbersome bureaucratic burden, promotes the use of local materials and helps transmit the technology that contributes to making reconstruction sustainable.

Likewise, the distribution of subsidy in three tranches upon inspection of quality of construction as well the introduction of a banking system to facilitate grant disbursement vastly decreased any foul play. The dissemination of authority to the local government after its formulation has boosted the perception of ownership of the process and will certainly help in institutionalising the efforts. A huge amount of the resources has been utilised in training the construction workforce and orienting the people on quake-resistant construction.

Worldwide, rebuilding is observed to be a very complex, dynamic and demanding process with multitude of adhering factors. The lessons learnt from similar disaster-affected countries show that a blend of bottom to top approach comprising onsite technical assistance, capacity enhancement and awareness raising strategy is essential to sustain the achievements of reconstruction. It is now also important to focus on institutionalising the achievements of reconstruction as well as replicate what has been learnt in non-affected parts, considering the earthquake risk in Nepal.