Slippery slope in Nepali banking: Need of rescue

The mid-term review of the Monetary Policy guides BFIs to consider only the weighted average of the interest rates on deposits and loans while calculating the spread rate and exclude the investment made by the banks on government securities

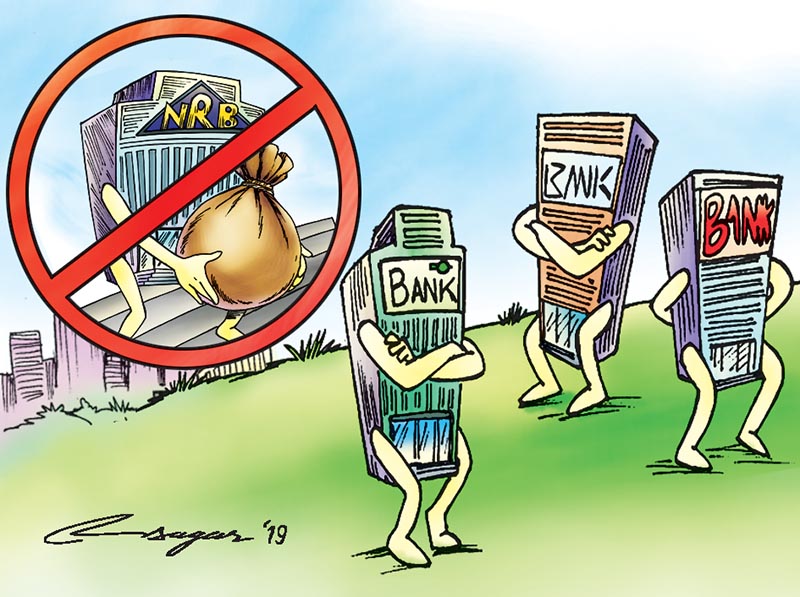

Are bankers turning into shrewd magnates? The recent hue and cry over interest rates on loans has been targeting bankers, and has resulted in substantial slow down in their earnings. Disgruntled industrialists are demanding that the interest rate on loans extended to productive industries not exceed 7 per cent and the rate on commercial loans not be higher than 9 per cent. The interest rate is being considered as the prime bottleneck that got entrepreneurs into the mess. There’s no gainsaying that banks and financial institutions (BFIs) are making profits, while small and medium industrialists are on the verge of closure due to the high interest rates on loans and advances. Industries and banks need each other vehemently, so do they a solution at this moment.

The central bank takes stern action only if the banks go against its regulatory limit on the spread rate. In a liberalised financial regime, it cannot exert pressure on the bankers. However, it has the duty to look into the situation closely and take appropriate action when need be. But somehow or the other, we all need to look at the ground reasons of the imbroglio and find out the right solution before it’s too late. A robust financial system neither welcomes a cat-and-mouse situation nor tolerates a hide-and-seek game between the regulator and BFIs. Starving industries in Nepal are crucial in generating employment opportunities and stimulating the national economy. But nothing is likely to happen anytime soon. Nepal needs more investment to rebound its melancholic economy rather than being focussed on incongruous arguments.

Questions are now piling up amongst the business community whether the profitable limit is crossing the normal profit margin that businesses make in Nepal. Entrepreneurs opine that they hardly earn 10 per cent as their return on investment, whereas the banks enjoy a whopping 30-plus per cent margin. So what is the regulatory limit on the profitable margin in Nepal?

According to the Black Marketing and Some Other Social Offences and Punishment Act of Nepal 1975, if a person trading in any goods has made profit in excess of 20 per cent normally, such a person may be punished. However, Nepal’s trading houses make double this limit and even go up to 100 per cent.

What about services? Is it justifiable to make as much money as one can? Or should there also be a limit? And who is to establish this benchmark at a time when the nation is trying to accelerate growth in a liberalised economic system?

However, there are some grounds for lowering the rates. In a normal sales strategy, when the price is high, the expected quantity of produce to be sold is low. But rates need to be cut where the expected quantity is targeted high, as far as consistent growth is concerned. This means bringing the population into the sales bracket, and fixing the profitable margin low. This applies equally to tax revenue. The government may slash the tax rates but brings more individuals or entities into the tax bracket. Suffice to say, banks may cut the rates if the base of the financial consumers increases. Financial access is accelerating growth of formal financial products. This should stimulate banks to keep the margin in balance so that business and industry can run smoothly without having additional burden and fearing of volatility.

While industrialists vented their anger on the bankers for being adamant on the steady interest rates like a cartel, there is no scope of carrying out such malpractices. Bankers opine that they cannot bring the interest rates down as the interest rate offered on the deposit is still high. This panic will create a havoc, which may spark unhealthy competition in the near future.

This trend is a matter of great concern, and what is worse is that there is no panacea for tackling it. A system at times is governed by people’s sentiment. At one point, industrialists went to the Prime Minister’s residence with a plea to reduce the interest rates. It’s now the bankers’ turn to be there. The central bank, by and large, is in between these two: government and banks. As a sigh of relief, the recent mid-term review of the Monetary Policy guides banks and financial institutions to consider only the weighted average of the interest rates on deposits and loans while calculating the spread rate and exclude the investment made by the banks on government securities. This is a new option that the central bank has used through its regulatory rights to reduce the interest rate charged on loans.

For the central bank, there are no grounds to guide banks to modify the interest rates overnight. The regulatory directive is such that the banks can modify their rates on a quarterly basis only. And the interest rates in a perfect market feature are solely attached to the market. That means the interest rates are primarily fixed by the demand and supply of funds. The base rate is the minimum benchmark of the cost of the capital, which guides the banks to fix the interest rates on lending.

The central bank tone moves targeted growth, as it controls policy actions and economic robustness. Responding to the disgruntled bankers on their understanding of the recent Monetary Policy is its own regulatory tone. This is essentially a generic policy tool that supplements the inherent norms of being the central bank.

Giri is Deputy Director at Nepal Rastra Bank