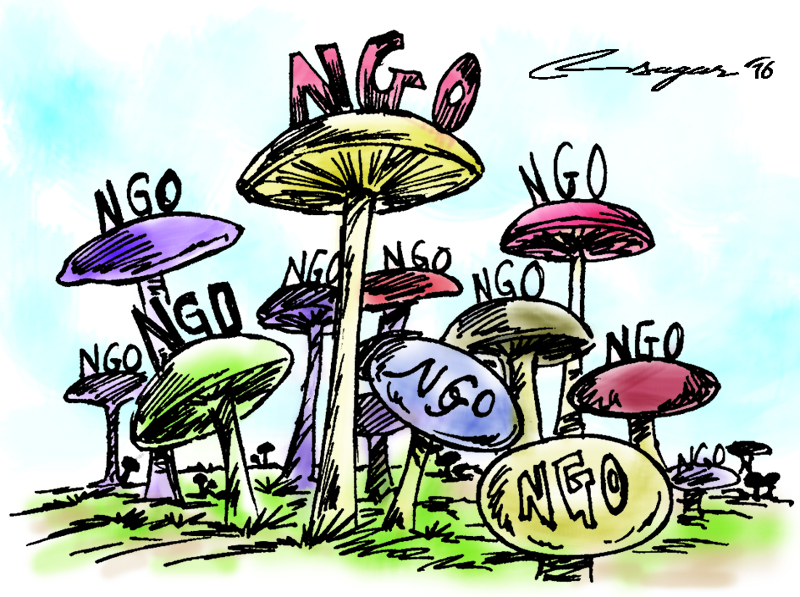

NGOs under scrutiny: Unjustifiable distribution

Maintaining the financial transparency and fairness in work are essential to ensure trustworthiness of NGOs. The government has to develop a system to monitor the financial growth of the people engaged with NGOs

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are now recognized as key third sector actors on the landscapes of development, human rights, humanitarian action, environment, and many other areas of public action.

NGOs are best-known for two different, but often interrelated, types of activity the delivery of services to people in need, and the organization of policy advocacy, and public campaigns in pursuit of social transformation.

NGOs are also active in a wide range of other specialized roles such as democracy building, conflict resolution, human rights work, cultural preservation, environmental activism, policy analysis, research, and information provision.

What constitutes an NGO, and the challenge of analyzing the phenomenon of NGOs remains surprisingly difficult. It is because NGOs are a diverse group of organizations that defy generalization, ranging from small informal groups to large formal agencies.

NGOs play different roles and take different shapes within and across different societies.

The work undertaken by NGOs is wide-ranging but NGO roles can be usefully analyzed as having three main components: implementer, catalyst, and partner. Considering its nature of the engagement in society, NGOs are termed variously in different society.

Community Based Organizations (CBOs), Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), Voluntary Organizations (VOs), Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs), Charity Organizations (COs) are some commonly used names for NGOs.

In this light, NGOs in Nepal also resemble many of the basics of the NGO principles; wide range of activity area, engaged in society as implementer, catalyst and partner, and basically formed by non-government stakeholders.

However, when kept in the tough scrutiny, there exists many contradictions and also multiple by-products of such contradictions. Some of the mismatch in the true essence of NGOs and the things happening in our society are discussed in this article:

NGOs are meant to serve the people in need. The people of remote villages where the government deliveries are poor need more NGOs to ensure people’s access to services.

However, NGOs in Nepal are more concentrated on comparatively developed areas. The data show that 24841 NGOs are in central region out of total 39759 NGOs registered with Social Welfare Council.

Only 2551 NGOs are working in Far Western Region which is the least developed region with the least Human Development Index in the country. This fact best portrays the concentration of NGOs where the human development index is comparatively better.

We cannot simply believe that the HDI in Central region is better because of the engagement of more NGOs in this region.

The engagement of NGOs in developed region is further justified by the fact that 12687 out of 24841 NGOs operating in the Central region are concentrated in Kathmandu, the district with the capital city and the highest Human Development Index.

NGOs are formed by a group of civil people with the intention of working for social development, in some senses for social transformation. People understand their problem as well as their need at the local level.

In order to fill up the gap between problem and need, people help each other making their self-help group, which is what a NGO is. Ranging from mothers’ group in various parts of the country to so-called large NGOs working in national level this dilemma is seen in their orientation.

If proper intensive research is carried out it may not be surprising if we find that many NGOs in Nepal have their Board of Directors from the same family or close relatives as if it was just a private or family business; membership to the outsider is denied or limited. They lack transparency in terms of financial and service delivery issues.

NGOs provide more remuneration to their staff; the salary and benefit is more to them than to those working in government service or in private companies.

Are the funds collected out of the plight of poor and needy people meant to be spent in higher salaries and benefits to NGO staff?

The NGOs running out of charity and donation are found to be spending large sums in increasing use of expensive luxurious vehicles and personal benefits by high ranking officials of those NGOs.

There is no transparent and reliable recruitment process in many NGOs except for some reputed national level NGOs that claim to have scientific Human Resource Management system within the organization.

Though there is a provision that NGOs need to announce vacancy publicly, very few do so. Nepotism and favourism are rampant. Many NGOs have developed bylaws to suit their unqualified relatives.

NGOs are important stakeholders of social development in the world and in Nepal too. Nepal needs a strong monitoring agency for NGOs. Maintaining the financial transparency and fairness in work are essential to ensure trustworthiness of NGOs.

The government has to develop a system to monitor the financial growth of the people engaged with NGOs and ensure that NGOs and its workers are righteous and devoted to service than to benefits.

Fairness in recruitment and career growth of employees in NGOs needs to be guaranteed in NGOs with some mechanism like the one in the government system -- the Public Service Commission.