Menstruation: Let’s not make it taboo

The more we talk, the more we stop identifying menstruation as a problem. The change will occur only when we internalise the problem and take responsibility to make girls feel comfortable and safe in their schools

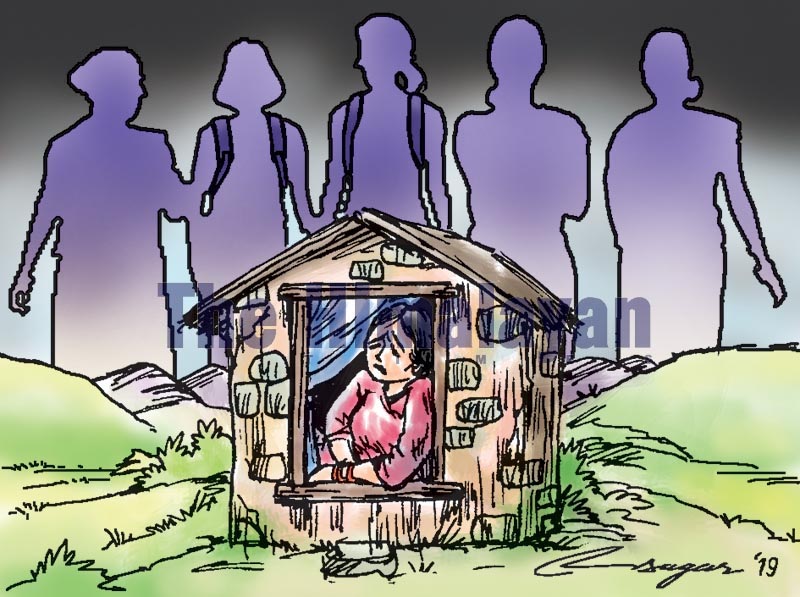

One beautiful summer day as I was about to take my eyes off the window, my colleague entered my office with a surprised look on her face to tell me what she had recently read about chaupadipratha. She asked me if young girls and women in Nepal are actually dying because of it. If I also had been on a similar situation, isolated in the cowshed, not allowed to eat any nutritious food, go to the kitchen, see male members of my family and was prohibited from attending school during the menstrual period.

With her overwhelming questions, I choked up a little and felt embarrassed. I felt like someone had just hurt my identity or devalued where I came from. Her questions had also unlocked some of my troublesome early adolescence memories.

I vividly remember the day I got my first period when I was about twelve years old. I was in school when I realised that I was bleeding. In a panic state of mind, I rushed out of school without telling any of my friends what had just happened as mensuration communication was almost taboo. I found myself sitting beneath a tree near my house, desperately trying to contain and hide the blood on my skirt and not knowing what to do next or where to pgo. Despite having an educated family, my elders never once talked about managing periods, neither did we cover this topic in school, and none of my female friends or cousins had conversations about it. Rather, the only information I was provided at this point was that I would be impure and untouchable, forget about the stabbing abdominal pain and cramps.

I was a talented kid with perfect attendance record at school. But now that I have my period, I was worried about the classes I would miss for about 11 days and how the boys in my class would react to my menstruation. My menstruation experience left an overwhelmingly negative effect on my self-esteem and confidence during my early adolescence.

According to UNESCO statistics, three out of ten girls miss school in Afghanistan and Nepal during the menstruation period, a prominent factor contributing to school dropouts. In Nepal, particularly in rural areas, girls neither get the necessary information from their families nor do their teachers in school discuss menstrual management, which impacts negatively on their mental, physical and emotional wellbeing and put them at a greater risk of dropping out from school.

My research in Mugu titled Delivering School Education in Mugu District (2012), published by the International Geographical Union Commission on Geography of Governance, showed that the dropout rate of girls for grade 6 was 20.5 per cent. Overall dropout rate for girls in grades 6 to 8 was 16.3 per cent. Some of the contributing factors of dropouts among school girls in Mugu were the concept of impurity or untouchability during menstruation, lack of menstrual management knowledge and lack of toilets in the school. Research showed that most of these girls had gone through traumatic experiences, anxiety and embarrassment. Some girls believed that God would get angry and punish them if they were not to follow the set taboos while others could not tell anyone about their first few periods due to the fear of being absent in school, having to stay at a cowshed alone and the humiliation and embarrassment among school friends. No wonder, these girls choose to leave school once they hit puberty.

A simple calculation shows that an adolescent girl in western Nepal has to stay in a cowshed at least 60 days per year based on the 5-day menstruation cycle and might miss around 50 days of school based on the 10-month academic calendar. Likewise, if we assume a woman starts her menarche at the age of 12 and menopause at 51, she will have menstrual periods around 468 times and spend almost 6.5 years menstruating in 39 years. Even with these simple facts, we do not feel comfortable talking about menstruation. Therefore, until now in the 21st century, there is a deeply engrossed belief of impurity.

Though a few positive changes are already to empower girls, including a mentorship programme, sanitary pad-making workshops, distribution of feminine hygiene kits, and also provoking advertisement products, such as “Wai Wai”, to spread awareness, an absence of communication and discussion in families and schools is seen in rural Nepal. Without recognising these issues as female issues, every father, brother and uncle must be willing to proactively speak up to eradicate such stigma and taboos. The more we talk, the more we stop identifying menstruation as a problem. The change will occur only when we internalise the problem and take responsibility to make girls feel comfortable and safe in their schools. With this collective effort, it is indeed possible to reduce dropout rates and shape the future of our adolescent girls, which will have a trickle-down effect in every aspect of their lives.

Michelle Obama stated in her popular book “Becoming”, that “I’d gotten my period, which I announced immediately and with huge excitement to everyone in the house because that was just the kind of household we had.” I hope we can create a similar environment for our girls one day that they do not feel ashamed of their natural biological process. Can we create a similar environment for our daughters and sisters at home and school too?